A mother’s letter to her sister

The Day Little Emma Jane Robinson left this world.

|

S |

o many times those of us who do such things, will walk through an old country graveyard, often noticing the monuments of young children, lost at painfully early ages to generations of long ago, before the advent of modern medicine. We marvel at the large families, and almost every one of these having lost one, two, three or more children. We shake our heads at the mere thought of these losses, unable to imagine the grief surrounding such occasions. Here is a first person account of one such loss suffered by a New Hampshire family from another century. It is a letter my great, great grandmother, Frances Eliza Weld Robinson (1831-1906) wrote to her sister Elvira Weld. My mother says her grandmother, Victoria (1854-1932) often mentioned the passing of her younger sister, and that the family never got over it. Of course they didn’t. – Dean Dexter

Meredith, New Hampshire, January 9th 1864

Dear Sister,

I suppose you received a dispatch from Mr. Ladd[1] last Monday saying that dear little Emma was no more, knowing you would be anxious to hear more particularly, as to her sickness and death, I thought I would try to write you. She died last Sabbath a quarter before twelve of that dreadful disease – diphtheria.

Was it not strange that she be taken away by the very disease that she feared so much? She was taken sick Tuesday night with the earache, but as she had that so much we did not feel alarmed. Wednesday she was very feverish and in the afternoon and through the night she did not have her senses. Thursday she seemed better, in fact I could see nothing but that she was doing well, except that she threw up her food.

Friday forenoon she said her throat felt some sore. I put a flannel on it, but did not think of diphtheria, nor feel alarmed. I thought perhaps she had taken some cold, being up so much the night before.

Friday night she was so sick all over, that her father went for the doctor[2] in the morning. He examined her throat at once, and pronounced it very bad, the throat and left part of the mouth was nearly covered with canker and a membrane formed in the throat. He told us what to do for her, as well. So he could, but as he has never had a case of the kind, he did not know as well how to treat it.

I do not think, though, that any doctor could have saved her. She grew worse all through the day and night. When the doctor came in the morning, he said he would try outward applications of ice and gargle the throat with salt and water. We tried that, but it was entirely useless.

She sank rapidly away till a quarter before twelve, when she was released from her sufferings. O! How much I wish you could have been here. It would have been such a comfort to her as well as us. The dear child had her senses as clear as when she was in perfect health till the last moment.

Sometime between ten and eleven, her father carried her into the parlor as the doctor thought it best to have her away from the other children, and we thought she might live through the day. He then went to the barn.

She called me to her and asked for her father. I told her he was at the barn. She said, “Tell him to go after my little sister as quick as he can for I think I shan’t live and I want to see her and before I die (Victoria[3] was at Jane’s* [4] ).

I told her I hoped she would live and asked her what made her think she would not. She held up her little hands, the blood already settling under the nails, and wanted me to look at them.

You cannot even imagine my feelings.

“Mother,” she said. “I am dying now.”

I asked her if she was not afraid to die. She said no, but she wanted me to go with her. I talked with her as well as I was able, and tried to reconcile her to parting with us. She then wished her Aunt Emily[4] to get the Bible and read it to her. She read some verses to her from the twenty-first chapter of the Revelation. She then gave away her things and told where she wanted to be buried.[5]

She wanted me to pray that she might live. I felt so I could not speak. She then commenced praying for herself, and to my dying day I shall not forget her words. It was enough to draw tears from the hardest heart

“Dear Lord, do please to let me live; bless me and let me live!” was the burden of her prayer.

Mrs. True[6] came not more than ten minutes before she breathed her last. She said, “Aunt Mary, do you think I am dying?” She then also inquired of Emma.[7] After that she wanted me to sing “Happy Land.”** I told her I could not sing, but I said one verse for her.

She asked her Aunt Mary to sing, but she could not. She died very easy. Doctor said he had no idea anyone could suffer so little in dying of that disease.

The darling child is no more for God has taken her to himself.

We miss her busy active form and no longer count four little ones around our hearthstone, yet much as I loved her I have not felt to murmur, or repine that God has taken her to himself. As I told her when she was dying, “God loved her too well to let her stay any longer in this world of trials and sin.”

I have filled this sheet with an account of Janie, as I thought that would interest you more than anything else.

We had an artist come on Monday and take Janie’s picture. We also had Victoria and Josie[8] taken. If I could see you I could tell you many things that I have not space to write. When Janie was dying she wanted to write to you and Grandma Weld that she had the diphtheria.

Write soon.

F.E.R. (Frances Eliza Robinson)

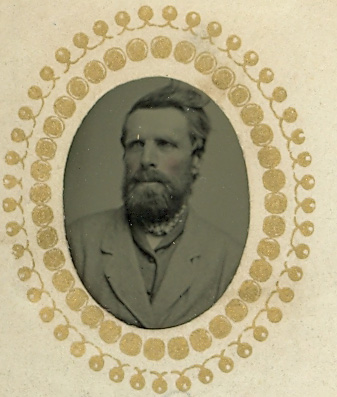

Portrait believed

to be Emma Jane Robinson

[1] Mr. Ladd is John Sturtevant Ladd, Emma Jane’s uncle, the husband of Sarah Jane Robinson, sister of Joseph Wadleigh Robinson, Emma Jane’s father.

[2] Dr. Noah Lawrence True, who lived in the second house to the southeast of the brick home later owned by Morrill Scott Swain, and later his cousin, Ansel Higgins, now situated on Higgins Road, Chemung section of Meredith Center, NH.

[3] Victoria is Helen Augusta Victoria (Robinson) Swain, oldest daughter of Frances Eliza and Joseph Robinson and older sister to Emma Jane. Victoria was away, with her cousin Jane,* her Aunt Emily’s daughter.

[4] Aunt Emily Weld, sister of the writer (Emily Howard Weld, Mrs. John Tyler Sanborn. Victoria was with her daughter Jane* at this time).

[5] Emma Jane is buried in a little private cemetery in a field on the Robinson Farm, which has been in the family since 1790, now owned by John Robinson.

Emma Jane would be John Robinson’s great aunt, two generations back.

[6] Mrs. True, Dr. True’s mother, widow of one Abram True. She was the sister of Nancy B. (Lawrence) Robinson, hence called by the children, "Aunt Mary."

[7] Emma, Dr. True's daughter.

[8] Josie is Josephine Robinson Roe, younger sister of Emma Jane, who later transcribed her mother's letter. Known as "Aunt Josephine" among the family,

she earned a PhD in mathematics, taught at Berea College, Berea, Kentucky, and Syracuse University, New York. She is listed as a "Pioneering Women in American Mathematics"

published by the American Mathematics Society and London Mathematics Society, 2009 supplement: Web Link.

______________________________________

Father and Mother: Joseph Wadleigh Robinson and Frances Eliza Weld.

Frances Eliza (Weld) Robinson of Meredith Center, N.H., author of the letter, Born Boothbay Harbor, Maine, March 23, 1831, died Berea, Kentucky, January 29, 1906, to her sister, Elvira Weld (born Boothbay Harbor, Maine, May 25, 1837, died Syracuse, NY August 22, 1916) At the time of this letter, Elvira Weld resided at 10 Salem Street, Charlestown, Massachusetts.

Father is Joseph Wadleigh Robinson (1817-1886).

Emma Jane Robinson, called “Janie” Born, January 5, 1856 died January 3, 1864 just eight years nearly to the day. She was a 9th generation descendant of Mayflower passenger, Degory Priest.

Two days later, Frances Eliza (Weld) Robinson, author of the letter, gave birth to her second son, Francis Joseph Robinson, on January 11, 1864.

**Happy Land

Children’s hymn lyrics by Andrew Young, music by S.S. Wesley

“There is a happy land, far, far away,

“Where saints in glory stand, bright, bright as day

“Oh! How they sweetly sing, Worthy is our Savior King,

“Loud let their praises ring, Praise, praise for aye.”

Helen Augusta Victoria (Robinson) Swain, oldest child to Joseph and Frances (Weld) Robinson who said the family “never got over” Emma Jane’s passing

_________________________________________________

Private Robinson Family Cemetery, Robinson Farm, Chemung Road, Meredith Center, New Hampshire, resting place of Emma Jane Robinson

Dr. Josephine Robinson Roe (1858-1946), transcriber and preserver of her mother's letter. Dr. Roe served as Dean of Women at Berea College, Berea, Kentucky, as well as professor of higher mathematics there under the administration of William Goodell Frost in the early 1900s, before joining the faculty of Syracuse University, where her husband, Dr. William Drake Roe (1859-1929), was a mathematician and astronomer. They resided at 123 W Ostrander Ave., Syracuse, NY 13205 where he had installed a personal observatory, the outside structure of which still stands at this writing. The contents of this observatory, considered one of the finest private such facilities in the world at that time, were donated to Harvard upon his death.

Posted June 7, 2012

Return to NH Commentary Home Page